Abingdon House and the Catholic University College

To the west of Wright's Lane at its south end lies Cheniston Gardens, a dour little development promoted between 1879 and 1885 by the Kensington building partnership of Taylor and Cumming. The site had previously been occupied by Abingdon House, one of the several Georgian ‘villas’ with ‘grounds’ to be found hereabouts before the coming of the railway. In a brief but eventful episode of the 1870s, Abingdon House became the Catholic University College, until that institution collapsed ignominiously and its site was redeveloped.

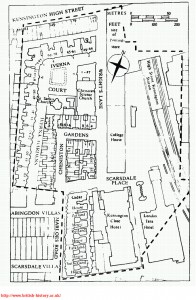

This site was one of the two properties in Browman's Field which were acquired in 1720 by Sir Isaac Newton and passed in 1753 to Gregory Wright (page 100). A lease of the land, then being used as ‘garden ground’ but with a small house in the south-west corner, expired in 1766. (ref. 58) At an unknown date the house was much enlarged or rebuilt; Starling's map of 1822 shows it then to have been a good-sized house close to the west corner of the east-west section of Wright's Lane, roughly on the site of the present Nos. 40–46 (even) Cheniston Gardens; to its north and east lay some two acres of walled garden (Plate 2a, fig. 33).

By 1841 Abingdon House had acquired its name (in reference to Abingdon Abbey, the ancestral owner of Kensington parish church). It was in the freehold ownership of the Alexander family as ultimate heirs of Gregory Wright, and was let on short term. (ref. 59) At least two tenants of some standing lived here (the fourteenth Lord Teynham, c. 1838, and Marmaduke Wyvill, M.P., 1861–2), but in the 1840s it was briefly a ‘ladies’ school’. (ref. 60) At one stage, perhaps after Wyvill, the house ‘was occupied by the widow of a ci-devant Indian potentate of high rank, with her Hindoo servants and retainers. A local rumour … says that during the residence of the Ranee at Abingdon House it was the scene of Hindoo religious ceremonies, and even of sacrifices, that were practised by the inmates.’ (ref. 61)

In 1869 Herbert George Goldingham, a solicitor of Worcester, took a long lease of the house and garden from David Henry Alexander. Goldingham's firm had been involved with William Nokes (a tenant of Abingdon House during the 1850s) in developing parts of the land to the south and west (page 225). No doubt influenced by the advent of the railway, he had plans prepared by J. M. McCulloch (a surveyor-architect involved on this neighbouring property) to form a street here to be called Ravenhill Gardens, on similar lines to the eventual Cheniston Gardens. (ref. 62) But this plan did not proceed, and Abingdon House declined into ‘a neglected and ivycovered ruin’. From this fate it was rescued, if only fleetingly, by Monsignor Capel's project for a Catholic University College.

This establishment emanated from a decision ratified by the English Catholic hierarchy in August 1874 to provide ‘a College for more advanced studies for the higher classes of the laity’. (ref. 63) Cardinal Manning having in 1868 moved his archiepiscopal seat from Moorfields to the ProCathedral of Our Lady of Victories nearby, a site in the vicinity was deemed desirable for this ambitious project. The prime mover was Thomas John Capel (1836–1911), a fashionable Catholic prelate. Capel enjoyed the approbation of his co-religionists and the enmity of their opponents for his cleverness in converting high-ranking Protestants. His most famous triumph was the ‘perversion’ of the third Marquess of Bute, which earned him a preferment from Pope Pius IX and a niche in English literature as the casuistical Monsignor Catesby in Disraeli's Lothair. He was prominent in London society, ‘loved good food, good wine and every kind of little luxury’. (ref. 64)

From about 1869–70 Capel was attached to the Pro-Cathedral and living at Cedar Villa, at the bottom of Wright's Lane opposite Abingdon House. In November 1872 he was reported as having bought Abingdon House for use as a Catholic day-school. This seems to have been the start of the school which he set up more formally at Earl's Court in 1873 (page 331) and which he saw as a ‘feeder’ for the more ambitious Catholic University College. (ref. 65)

With energy and zeal, Capel brought the new college into being early in 1874, when an ‘iron building’ was erected in the grounds of Abingdon House. (ref. 66) An embryonic senate was formed, including the Duke of Norfolk, the Earl of Denbigh, Lord Petre, and Sir Robert Gerard; funds were acquired, eminent Catholics (including the classicist F. A. Paley) were drafted in to serve the cause, and in October the college was quietly opened by Manning with a complement of seventeen students. A formal inauguration took place in April 1875, by which time the local Catholic architect George Goldie had fully converted the house to include an ‘academical theatre’, lecture rooms, library and museum of specimens (science interpreted according to Catholic doctrine by Professor St. George Jackson Mivart was specially emphasized in the curriculum). Just west of the house was a ‘temporary but handsome' chapel of corrugated iron and wood. In the same month, D. H. Alexander sold the freehold to the Duke of Norfolk, Lord Petre and Manning as trustees for the college. (ref. 67)

The college prospered for about four years. In 1876 numbers were up to thirty-six, the library and collection were advancing and the nucleus of a proper university seemed to have been established. (ref. 68) Then in June 1878 came disaster; Capel resigned and the establishment speedily collapsed. The official reason was debt. Certainly Capel had become deeply involved in the college's finances and owed money personally for the site and buildings of the school at Earl's Court. (ref. 69) Behind this, however, according to a later source, lay a scandal in which Capel's name was mentioned. (ref. 70) Allegedly the Vatican took a lenient view but Manning was not so indulgent, and Capel resigned. He appealed for help to the Duke of Norfolk, complaining bitterly of his treatment by ‘the Bishops’. ‘They leave on me the entire burden of finding the support of the College and the Students’, he wrote. ‘This I do by begging about thirteen thousand pounds, spending all I have had on earth about six thousand, as well as the paying of the necessary expenses incurred in giving hospitality … I have sacrificed family, social relations, sleep, and even the work of conversion … ’ Capel strenuously denied the charges against him as ‘calumnies’ which ‘have their origin in the spite and ill-will of a little clique.’ (ref. 71) He received some money from the Duke and others, but this could not prevent his bankruptcy in 1880 and the sale of his effects at Cedar Villa including pictures, a reliquary, fittings and candlesticks from his private chapel, and thirty dozen of wine. (ref. 72) The Catholic University College survived in name for a few years and then disappeared, along with the school at Earl's Court. Capel himself eventually left England and went first to Florence and then California, where he died. (ref. 73)

Source http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=50311

Bankruptcy Report Mgr. Capel

MONSIGNOR CAPEL'S EFFECTS.; A PRIEST'S PROPERTY TO BE SOLD

A marble bust of Mgr Capel mentioned in the property of Cedar House to be sold is likely the same bust that is now in the apartment of Coco Chanel on Rue Cambon,Paris, via her relationship with Arthur 'Boy' Capel nephew of Mgr. Capel. http://www.eclecticstyleblog.com/identified-the-bust-on-coco-chanels-mantelpiece/