An article about Boy Capel's Uncle printed in 1878

Celebrities at home (Volume 3). April 1878.

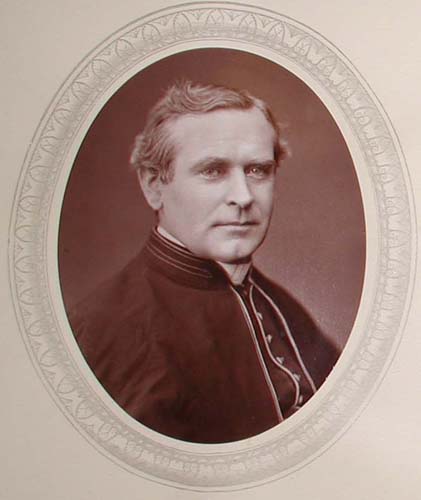

MONSIGNOR CAPEL AT KENSINGTON

The white house standling: in "Wright's Lane, almost shoulder to shoulder with the hideous red-brick Hospital for Boys, has undergone a change of late years both as to its title and its tenant. It was called 'The Cedars,' what time those trees were represented in the plural number; but now that only one magnificent tree remains, the accurate ecclesiastic who dwells there prefers to call his home 'Cedar Villa'. The previous tenant was not troubled by scruples of this, or indeed of any other, kind, when fun and frolic were to be promoted. Before his guests arrived he would take a piece of soap and mark his largest miror with a compound fracture, and on entering his dining-room would profess unbounded indignation at the carelessness of servants. It was at the Cedars that was arranged the elaborate series of anti-Davenport Brothers' experiments, which enabled the creator of Lord Dundreary to utterly demolish those dreariest of dull deceivers. But Mr. Sothern and his practical jokes have long since vanished from Wright's lane; his billiard-room has been converted into a richly-decorated chapel; the place where his cues stood is ingeniously packed with gorgeous vestments; the odour of his huge cigars has been exchanged for that of benzoin, frankincense, and myrrh; and that most popular of Roman Catholic ecclesiastics, the Right Reverend Monsignor Capel, D.D., reigns in his stead.

In the cosy room with the bay-window looking, not towards Wright's lane, but on the solitary cedar standing in a rolling sea of verdant lawn, sits a cleanly-shaven gentleman, endowed with good looks and an unmistakable air of distinction. The thick gray hair — very gray for a man of forty-three — is thrown well back from a well-shaped forehead. Beneath a bushy or rather bristly pair of eyebrows gleam a pair of noticeable gray eyes; from a well-cut mouth proceeds a voice naturally rich and powerful, and trained to express the most dehcate shades of thought or emotion. A priest's cassock, relieved by purple edging and buttons and a broad purple sash, — the insignia of the Prelature, — covers a strongly knit frame, slightly given to burliness. On the table lie books of a purely secular sort — the last new novel, the last book of travel, illustrated story-books, and the Autohiograpliy of Jolin Stuart Mill. On the walls are a few pictures of a devotional character, and an admirable portrait of the late Pope, in whose favour the master of Cedar Villa stood high, both as preacher and theologian. Monsignor Capel is very much in earnest at this moment, for he is explaining to a little knot of friends, of whom nearly half, by the way, are Protestants, his hopes and plans for the Ladies' Home in Kensington-square. As one listens to him, the conviction grows that he is a man who chooses to express himself rather accurately than showily, although the flash of the gray eye reveals the fire of eloquence that Iurks belind it. In admirably modulated tones he explains his views concerning that which he designates 'intelligent charity.' By no means disposed to check the open hand which showers a promiscuous dole to the poor and wretched, he holds that his work is essentially different from this — that his task is to see that those needing help really receive it in such form as to be of permanent benefit to them; that it is of no use for him to help them on to the first step of the ladder without taking some care that they do not slip off again into the Slough of Despond. More than this : his comprehensive scheme of charity embraces more than the absolutely wretched — the poor who have sunk so low that it is ungrateful work to try to fish them out of the depths and bring them to the surface. He expresses a strong opinion that all gifts should not be flung to the lowest, but that 'intelligent charity' should look sometimes on those who, without being filthy and starving, yet lead hard lives in the endeavour to do their duty and live cleanly. He has faith in the doctrine of helping those who attempt at least to help themselves. Pity, according to his creed, should not be reserved entirely for the hapless and vicious waif, its drunken father and drunken mother. Something should be done for poor but decent people, who send their children to the Board Schools, but yet have a hard and bitter time to make both ends meet. Hence the establishment in Kensington-square, at once a temporary home for indigent ladies, a school of dressmaking, and a training kitchen for servants. The indigent lady is most difficult to help. She is often not sufficiently well educated to be, in these days of high pressure, worth her board, lodging and clothing in any scholastic employment. She is hardly fit for a housekeeper, and exercises all the ingenuity of the committee to place her in permanent shelter. Poor girls of less ambitious pretensions are taught to make dresses, but some qualifications are demanded from them. Before admission they must fulfil the requirements of the School Board, and must also be proficient in plain sewing. Then they are handed over to the_ care of two dressmakers imported from Paris — Monsignor Capel holding that, whether the matter in hand be dogma or dressmaking, the best staff procurable is a sine qua non of success. Yet charity is not the special mission of the eloquent preacher who attracts Protestant listeners to the pro-cathedral. 'Teaching is my particular pleasure. I have long been engaged in the work of education, and have a passion for it' he says. He holds that charitable work is good as a relaxation, that it is good also as a preventive against intellectual pride and hardness of heart. He thinks it well to spend two or three hours every Friday, and seven or eiglit on Saturday, in the confessional, and to listen every day to applicants for help, on the ground that 'it is well that our hearts and minds should be brought into contact with misery and poverty.' Nothing brings a brighter light into his eyes than a hint that, after all, his reputation with the outer world is that of a fashionable priest who has made some celebrated conversions. 'I hate a priest,' he rejoins, 'who is only a fashionable man. My life is spent in hard work. For a year and four months I have only dined out, except at public demonstrations, nine times. I cannot afford the time or the wear and tear of sitting up late; but I know that I have the reputation of doing so.' In general society Monsignor Capel, with equal tact and taste, while always recollecting that he is a minister of religion, never obtrudes his priestly functions. Such conversions as that of the Marquis of Bute and the Duchess of Norfolk naturally made a great noise in the world, and induced many Protestants to think that Monsignor Capel received a species of capitation tax from the Pope, as one of his friends puts it, 'as Caspar does from Zamiel.' Nothing can be more erroneous. The adhesion of wealthy nobles is of course prized by the Roman Church; the priest who converts them is valued as a successful soldier of St. Peter; he does his duty, and that is all. With appetite whetted for teaching by his early experience at St. Mary's College, Hammersmith, Monsignor Capel has thrown himself zealously into tlie work of founding the Catholic Public School for boys and for girls at Kensinofton, and the Catholic College. In this, as in other departments of his work, he has spared no pains to secure a strong working staff. Having been born in the Roman Church he is less fettered in the choice of professors than a convert from the English Church would necessarily be. A born Catholic is not called upon to make that profession of uncompromising zeal which is, or is thought by himself to be, incumbent upon the new brother. The man who has been successively private chamberlain and domestic prelate to Pio Nono is above suspicion, and uses the confidence reposed in him largely and liberally. The teachers in the boys' school are drawn with sole reference to efficiency from Oxford and Cambridge, from Roman Catholic colleges, from German universities, and the University of Paris. At the Catholic University College are found, side by side with such names as Mivart and Barff and F. A. Paley, those of Magnus, who is a Jew, and Oldfield, who is a Protestant. In the club or recreation rooms at the University the same liberal spirit prevails. All the chief daily, and most of the weekly, newspapers lie on the table in the reading-room, as well as those magazines which represent the most advanced stages of inquiry The library of the college is very large and admirably selected, and the scientific schools are as well appointed as the library; even a botanic garden has not been forgotten. The physiological department is, as might be expected, beautifuly arranged, and for all purposes of teaching is complete, including even the strange leaf-insects which lend so much strength to the hypotheses of Darwin and Wallace. It is almost needless to say that both college and school have been arranged with the idea of making Kensington a spot towards which Roman Catholic families of narrow means should gravitate for the education of their children. Much of the hard work thrown upon Monsignor Capel's shoulders by these institutions is got through in his working library, arranged, like every room at Cedar Villa, to let in abundance of light and air, two absolute recquirements of its master. His writing-desk is thoroughly characteristic of the man, the keynote of whose mind is organisation. The doors of the desk flung back are pigeon-holed, ticketed with exact nicety, and stuffed with innumerable papers. Not, however, for the sifting of these has been accumulated the valuable theological library which loads the shelves occupying three sides of the room, A glance at these precious volumes explains why secular works fill the drawing-room. The working library might aptly be called a theological armoury, where arms for attack or defence may be sought and found at the shortest notice. Side by side repose the weapons shaped and fashioned by the great masters of dogma, St. Thomas Aquinas, Suarez, and Lugo, from whose vast store the modern polemic selects the lance or shield best suited to his strength. On the farther side are the useful Questions Historiques and the complete literature of English Ritualism, from the first Tract for the Times to the present day. ' The wily ecclesiastic, who looks over into the Ritualistic orchard, and when he sees the fruit nearly ripe shakes the tree,' is especially proud of his profound knowledge of every shade of Puseyism, makes it his business and delight to watch every new development of Ritualism, and enjoys his reputation of wiliness very heartily. In his bedroom he has another library devoted entirely to the English classics handsomely bound. Opposite his bed are two rude pictures painted at Bethlehem, one of the Virgin and Child, and the other of the Saviour at the first consecration. It may easily be imagined that a preacher and lecturer with an arsenal of theology at his back leaves little or nothing to memory or to chance. Yet in his sermons he prefers to trust for the clothing, the mere words and illustrations, to the inspiration of the moment. The skeleton of thought is prepared and fitted together with wondrous precision, and then the argument is carefully written out. To the remark that it would be as well to write the sermon completely out at once, the eloquent preacher and precise teacher, who never passes a day without devoting at least one hour to the study of dogmatic theology, will reply that a written sermon becomes a species of essay, and that a good essay may be a very poor sermon. Besides, the essay is all before the reader, while the sermon must be recollected and the argument grasped as it is developed. This operation is not very simple to persons with minds too sluggish to trip lightly from syllogism to illustration and back again. Hence it is sometimes necessary in a sermon, if not to repeat, yet to restate, to resume, the argument, to drive it home and clinch it with a fresh illustration if the first have missed fire. It is an important part of the preacher's duty to look sharply to this, to watch the faces of his congregation to see whether they are dazed or convinced, on a level with the argument or hopelessly floundering in the rear. Should the latter be the case, it is his duty to enliven with illustration, to enforce with monition; in short, to employ that ornamental rhetoric which, so long as he can do without it, his good taste leads him to avoid. Precision is of the essence of preaching as of all other teaching, and the lucid arrangement of agument without rhetorical padding is the object to be aimed at.

Monsignor Capel is proud of the skill by which Mr. Sothern's sometime billiard-room has been metamorphosed into a chapel. His own taste inclines to the Gothic; but as the shape of the apartment would nowise accommodate itself to the exigencies of that style, he was fain to put up with the Italian. With a keen love of art, he has decorated the chapel with many choice works: the crucifix is a masterpiece; the figures on the altar are by Rossi; the dark face looking down upon it is a portrait of St. Francis of Assisi by Francia, next to which hangs a lovely 'Assumption of the Virgin' by Domenichino. After early mass the celebrant betakes himself to the lecture-room, and then becomes the victim of public cares until the hour of luncheon. From this, the important meal of the day, two household pets are never absent — a beautiful mocking-bird and a great collie dog, grown somewhat obese by over-petting, and wearing a collar marked with his name, 'Beppo, Friend and Protector,' and the address of his master. Beppo is a learned as well as an amiable animal. He will turn his nose up at the most tempting of biscuits if he is told that it comes from Prince Bismarck; he will swallow a crust if told that it comes from the Pope. He is the delight of the pleasant Sunday afternoon gatherings at Cedar Villa, and moves among the assembled celebrities with wondrous majesty, especially after his master has retired for an hour's rest and silence before again appearing in the pulpit.